Ngarunyalki purtangalki | Future Past

Joseph Williams Jungarayi

2 Nov

2024

2024

16 Nov

2024

From: The Art of Joseph Williams

Lévi McLean on Joseph Williams Future Past

“They were living near telegraph station at Seven Mile, getting closer and closer to colonisation”

– Joseph Williams

If the promise of John McDouall Stuart’s exploration and the Overland Telegraph Line proved an economic mirage for the colony of South Australia and its investors in the late 19th century - for the Warumungu it created a new modern world.

As Williams recounts, the colonial future that followed the Telegraph Line produced radical changes to the pre-contact socio-spatial patterns of Warumungu living and knowledge systems. The age-long practices associated with what Williams once described to me as the “traveling days” were coming to an end.

The established pattern of Warumungu land-use involved considerable mobility, except in times of drought which saw them camp near more perennial waters. The turning point was the drought of 1891-93, during which the pastoral boom of the 1880s came to a halt and the colonies languished under the financial depression of the 1890s. By 1900 the Warumungu had set up a permanent camp by the Telegraph Station, which was also offering rations for pastoral work and services rendered by them. This suited the anthropological team of Spencer and Gillen, as it provided them with ready ‘informants’ when they arrived at the telegraph station in 1901, where they worked closely with Warumungu. Williams mirthfully mused to Azura Nichols in a recent conversation regarding aspects of this show:

"Every time I go there [Jurnkurakurru] I think of them. That waterhole there is for our swimming, but it was their drinking water…When Spencer and Gillen came, they [the Warumungu] didn’t give them white people a break. They performed many ceremonies in two months…Spencer and Gillen didn’t get much sleep."

These events, says Williams, resonate in the art featured in this exhibition as does traditional cultural production of Central and Northern Central Australia.

As the artwork and words of Williams show us, for over a hundred years, the Warumungu experienced the Telegraph Station in contradictory terms of a double consciousness – of dispossession and repossession, of the loss of traditional patterns of life but the gain of modern patterns from which they would wrest a Warumungu modernism, and more recently, artistic revivals of this modernism. In a recent conversation on the title of this show, Williams refers to this as “future-past” – a re-modernism which is also present in his own work.

“You know [in the] past there was different way of doing it, body, earth and now in the future, the way we give story is different. A lot of it in the past was verbal and simple, you know ground drawings with your finger, dancing, singing, listening, and seeing. You might look at that rock and you think ah it’s nothing, but it’s got a big story that rock.”

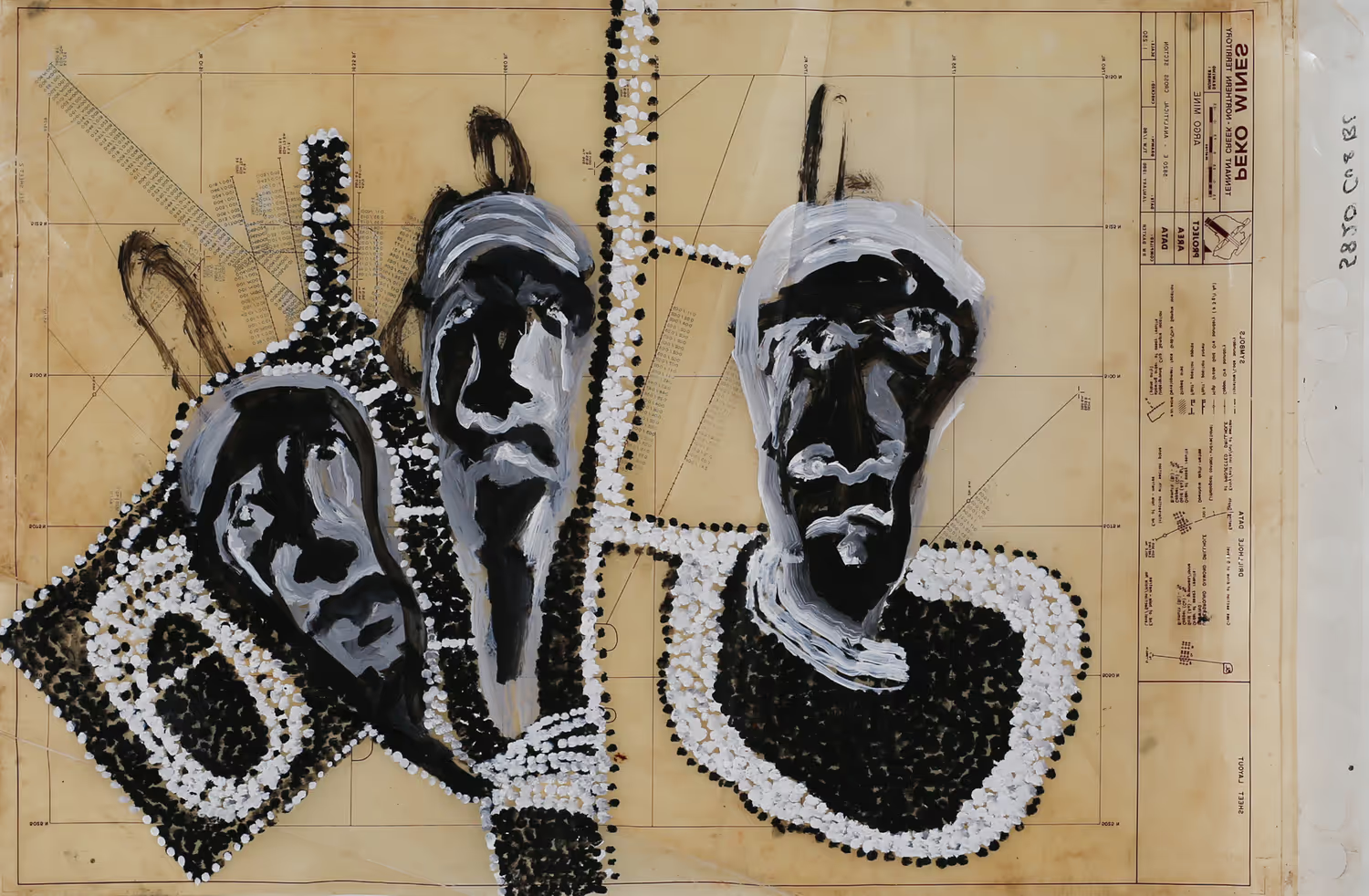

By utilising museum collections, schematic drawings depicting mining operations on Warumungu land, and detailed re-illustrations of Spencer's Warumungu photography, Williams unveils layers of the past interwoven with the present. This also doubles as an interrogation of the cartographic tradition and map-making practice employed by imperial powers to survey, represent, and assert control over their territories and colonies, emphasising political boundaries, resource locations, and strategic considerations but here repurposed or re-appropriated by Williams as a document of cultural interface from which wrests a modern Warumungu knowledge system. On the grids of the geosurveyor, these paintings superimpose a mythic world steeped in the past-future tense of Warumungu folklore and his own imagination to contest the impossibility of imperial space as a universalising entity, cognitively and physically.

The nature of knowledge and understanding of landscape are key themes in Williams’ art. By contrasting Warumungu iconography with that of the geosurveyors, he summons the spectre of earlier southern colonists as they attempted to cross the interior, often frustrated, or spurred on by the promise of water, as well as those of his Warumungu ancestors. His re-appropriations brings attention to the physical life and the physical features of the landscape elided by the calculus of the geologist's map.

Several of these works refer to different ways of knowing geological history, the surfaces and sub surfaces of the earth, and more widely to the different epistemologies or double consciousness of Western and Warumungu knowledge systems. Yet, at the same time, their intersection in this exhibition evokes the history of resource driven conflicts over water and gold which underpin the history of Warumungu relations with the colonisers for a century to come.

(Full version of text available in the catalogue).

Installation View

Artworks

Artist Profile/s

Joseph Williams Jungarayi

Lives

Joseph Williams Jungurayi is a founding member of the Tennant Creek Brio. He is a multimedia artist, carver, writer, poet and emerging cultural leader of the Warumungu community. Williams began his carving as a teenager during the mid 1990s, following in the footsteps of his grandfather Nat Jupurula Williams and being taught by his second grandfather Walter Pula Nelson. “They made them the hard way”, says Williams, with an axe and wood rasp, whereas Williams now utilises a range of modern tools on mostly hardwood to create various reinvented traditional objects including spears, shields, and boomerangs. His work includes paintings and a contemporary perpetuation of traditional objects including kayin (boomerangs), wartikirri (number 7 boomerang), clapping sticks and purnu (coolamons) fashioned from hardwood. He has recently begun experimenting with figurative realism, drawing inspiration from his Warumungu and Croatian heritage. Amongst other forays he co-directed (with Peter Pecotić) the film Countryman 2021, broaching his Croatian heritage and opened various exhibitions and launches with his singing and poetry performances.

Currently working for Nyinkka Nyunyu Art and Culture Centre he is also on the board of Desart, the peak arts body for Central Australian Aboriginal Arts and Crafts centres. Joseph believes in the value and success of the Brio as a role model for the younger generation. One of the last 20 or so remaining Warumungu speakers in Tennant Creek, he has worked as a translator (and natural spokesperson) for numerous publications and documents relating to the Brio and is a director for Papulu Appar-Kari Language and Cultural Centre.

Williams’ work has most recently been exhibited at his first solo show at Coconut Studios (Darwin) this year. As a member of the Tennant Creek Brio his work has also been exhibited in group shows, including: ACCA (2024), Biennale of Sydney (2020), Cassandra Bird Gallery (2024), Niagra Galleries (2023), cbOne (2022), RAFT Artspace (2023 & 2021), Modern Times Melbourne Design Week (2022), Croatia House (2020), Vincent Lingiari Art Award (2021).